By Tim Deeming, Partner, Tees Law, Medical Negligence, Cambridge and Gareth Owens, Chair, Aortic Dissection Awareness UK & Ireland

Following any tragic death there will be many questions which arise and many potential areas which need to be considered and explored, one of which may be that of an inquest.

We hope that this article provides some support to help anyone who may be affected by such circumstances. We are of course able to support any bereaved individual/family and provide education for clinicians and information for legal professionals: info@thinkaorta.net

Aortic Dissection

The aorta is the largest artery in the body and carries oxygen-rich blood from the heart to the brain, limbs and vital organs. Aortic dissection (AD) is a rare but life-threatening condition, where there is a tear in the inner wall of the aorta.

As the tear extends, blood may flow between the layers of the wall of the aorta, forcing the layers apart and creating a false passage or ‘lumen’. This can lead to reduced blood flow to organs and limbs, or to catastrophic rupture of the aorta.

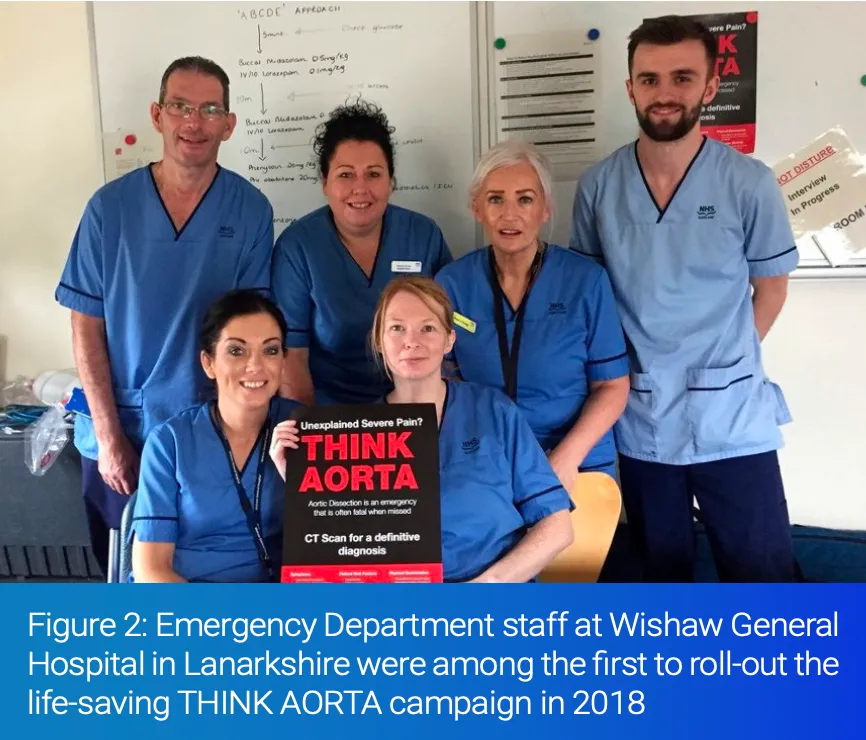

In 2018, data from national patient charity Aortic Dissection Awareness UK & Ireland showed that Aortic Dissection causes more deaths in the UK than road traffic accidents. The condition is not as rare as was once thought. The charity expressed concern that many of these deaths occur unnecessarily due to misdiagnosis and delay and created the patient-led THINK AORTA campaign and diagnostic strategy in partnership with the Royal College of Emergency Medicine (RCEM).

In 2020 the UK Government’s HealthCare Safety Investigation Branch (HSIB) published an investigation report2 confirming that delayed recognition of aortic dissection is a national patient safety issue, citing THINK AORTA as a diagnostic strategy and requesting action by the Royal College of Emergency Medicine and the Royal College of Radiologists (RCR). The two Royal Colleges worked collaboratively on their response and in 2021 published their first-ever joint guidance for medical professionals, “Diagnosing aortic dissection in the emergency setting”3.

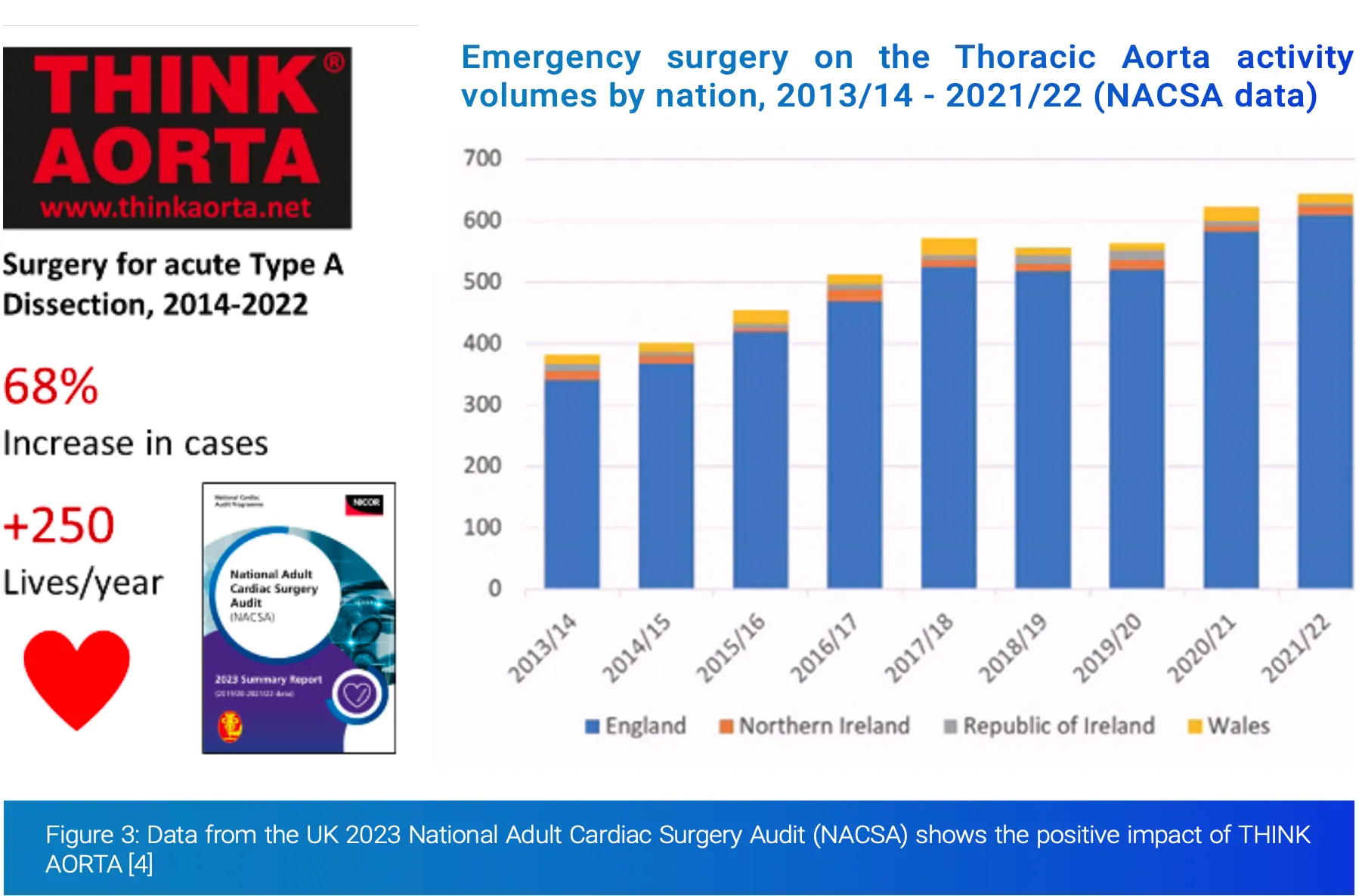

In 2023, the UK National Adult Cardiac Surgery Audit highlighted that, as a result of increased awareness and THINK AORTA, more patients are receiving emergency Aortic surgery, with a 68% increase in cases (250 more patients a year) since 20144. The national action and education prompted by THINK AORTA are transforming diagnosis of this disease.

Inquest Investigations

Following any death, the treating clinicians and independent medical examiners will consider whether the death was natural or not, and whether a death certificate can be provided at that stage.

A Coroner has a duty to investigate a death if they have reason to suspect that one of the following circumstances applies:

a) The deceased died a violent or unnatural death;

b) The cause of death is unknown;

c) The deceased died while in custody (e.g. in prison) or in state detention

As a result if the treating clinicians or medical examiner have concerns then they will refer the matter to the Coroner to consider. This does not automatically result in there being an inquest though, as a Coroner can make preliminary enquiries and then decide as a result of those enquiries that no inquest is required, because the duty to investigate further has not in fact arisen. One example of this might be where further evidence confirms that the death was due to natural causes, such as a post mortem.

Post Mortem

A post-mortem is an examination of the body by a qualified pathologist to assist in determining the cause of death and is arranged primarily by the Coroner, whilst of course bearing in mind the sensitivities of the family and any religious/cultural needs.

Most post-mortems are invasive, but there are increasing numbers being undertaken non-invasively, through imaging, although these are not available in many areas of the country, and may not exclude the need for potential samples to be taken to test for histology or toxicology. It must also be remembered that scanning techniques may not avoid the need for a more invasive post-mortem if, following receipt of the scan results, the Coroner decides that the more invasive type of post-mortem is required after all.

The Coroner will appoint a pathologist to conduct the post-mortem, who will be independent and they have the authority, if approved by the Coroner, to conduct tests and remove material that has a bearing upon the cause of death.

After the pathologist has completed their investigation the Coroner will usually authorise the release of the body to funeral directors so that arrangements can be made, if the Coroner is satisfied that the body is no longer required for the investigation. The pathologist will have provided a post-mortem report to the Coroner which should contain a detailed analysis of their findings and provide conclusions about the cause of death, so far as they are able.

If the family or another interested person is not content with the post mortem result then they can seek the Coroners authority for a second post mortem to be undertaken, at the requesting parties cost. This though is more usual where the death relates to a potential homicide. There is no absolute right or entitlement for a second post mortem as the Coroner has judicial discretion to take account of the reasons in support of a request and any competing considerations.

If, following their preliminary enquiries a Coroner decides that they are satisfied that the duty to investigate does arise then an inquest is likely to follow. The numbers of inquests vary across the country and Coroners are supported by their Local Authority, but nationally inquests occur in around 5% of all deaths. Following such preliminary enquiries then a Coroner may issue an interim or final death certificate, depending on the investigations and whether an inquest is required.

Inquest

The Coroner is not allowed or expected to make any finding relating to liability or negligence as a Coroner’s Court is not to allocate blame, or to establish civil/criminal liability, it is a fact finding investigation and will usually involve obtaining statements from the treating clinicians and family, as well as considering other available evidence which may well include the post mortem and toxicology results, and potentially independent expert evidence.

Often a Coroner will arrange for preliminary statements to be obtained from the family, the treating clinicians and for these to be shared and they may then arrange a pre-inquest review hearing. This can be held in person or remotely so as to ensure that a clear route is set out for the investigation through to the inquest so that the family are front and centre.

Where an inquest is being arranged it is often the case that the Hospital/GP/Interested persons will have legal representation and support and so families should likewise consider the same given the impact that this can have upon the investigation, as well as the emotional impact that any inquest will understandably have.

The areas which are often addressed at this hearing will be:

∙ Identity of Interested Persons

∙ Scope of the inquest

∙ Whether Article 2 engaged

∙ Whether jury required

∙ Matters for further investigation

∙ Provisional list of witnesses

∙ Disclosure

∙ Jury bundle

∙ Date of next PIR hearing

∙ Date of inquest; length of inquest

∙ Venue for hearings

And more infrequently it will include:

∙ Anonymity of witnesses

∙ Special measures for witnesses (including video links and screens)

∙ Public to be excluded for part of inquest (national security)

∙ Public interest immunity

∙ Apparent bias

∙ Need for an interpreter

∙ CCTV evidence

∙ View of the scene

∙ Other matters

At the inquest, which may also be held remotely or in person depending on the Coroners determination, it will usually be that once the Coroner has opened the hearing, witness evidence will either be read in by the Coroner where it is agreed, or witnesses will be called to give their evidence and understanding of the situation as they recall it. Questions can then be put to them by the Coroner, family and other interested persons but this is not cross examination, as it is not a trial. All persons should be assisting the Coroner in enabling the investigation to be full, frank and fearless.

Having heard all of the evidence the Coroner, or jury where required, will then determine the history of events as they find it and then look to complete the record of inquest which sets out the findings. We cannot set out all of the potential inclusions and impacts within this article, but the record will include:

1. The name of the deceased

2. The medical cause of death

3. How, when and where the deceased came by their death – which is usually a factual summary

4. The conclusion of the Coroner/jury – which may include any of the prescribed short form conclusions, a narrative conclusion, or an Article 2 inclusion

5. The deceased’s details for the final death certificate for the Registrar, so that a final death certificate can be provided

Learnings

One potential outcome from an inquest is that where the Coroner/jury believe that there were failings, and that sufficient improvements have not been made such that there remains a risk for other individuals, then a Coroner can issues a Regulation 28 request, more commonly referred to as a Prevention of Future Deaths report.

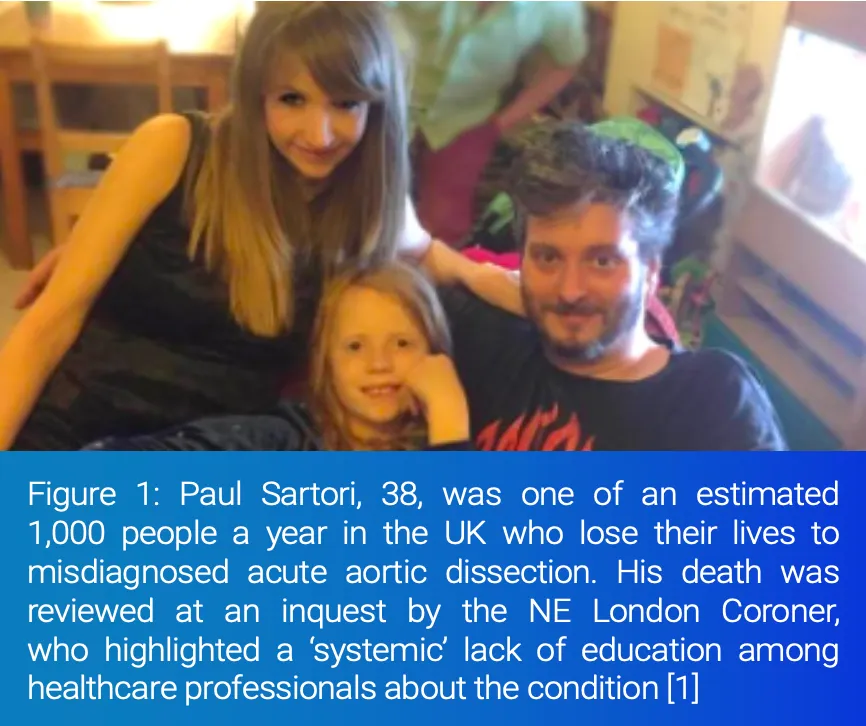

A Coroner cannot compel that action is taken, but can highlight areas of concern and Trusts will then have a duty to consider and respond to this. An example of such a request by the Coroner1 investigating the death of Paul Sartori was:

During the course of the inquest the evidence revealed matters giving rise to concern. In my opinion there is a risk that future deaths could occur unless action is taken. In the circumstances it is my statutory duty to report to you.

The MATTERS OF CONCERN are as follows. –

1. The Inquest heard evidence that the streaming guidance in place for A & E staff had not been updated to take into account the learning from the death and to take into account the guidance from the THINK AORTA Campaign (launched in 2016).

2. The nurse making the decision to re-direct the deceased from A&E did not record a full set of observations, to include a pain score, prior to diverting the deceased from the A & E department. The nurse did not document her decision-making process and rationale for redirecting the deceased from A&E.

3. A junior sister who provided evidence at the Inquest was not aware of the THINK AORTA campaign. The Inquest heard that the senior leadership team had recently agreed to embed the THINK AORTA learning into practice at all levels within the emergency department. This learning had not been embedded at the time of the Inquest hearing.

It is vital for all that learning is embedded to prevent/reduce risks arising again, especially by the time of the inquest, as everyone present will want to ensure that every practicable step has been taken.

Next Steps

The 2023 NACSA data shows that, to date, THINK AORTA has addressed roughly 25% of the estimated UK deaths due to misdiagnosed aortic dissection. As a diagnostic strategy, THINK AORTA has professional endorsement from the Royal College of Emergency Medicine, the Royal College of Radiologists, the Society for Cardiothoracic Surgery, the Vascular Society, the Healthcare Safety Investigation Branch and Heart Research UK.

What we know is that with prompt diagnosis and rapid transfer to a specialist Aortic centre, modern medicine can deliver excellent outcomes for a patient with acute Aortic Dissection. THINK AORTA has ushered in a new standard of diagnosis and care. The old clinical thinking, that this is an incredibly rare disease and patients do not do well, even if diagnosed, needs to be updated to reflect 21st century medicine and the new

standard of care.

Clinicians should seek to educate themselves and their colleagues about THINK AORTA, using the RCEM/RCR professional guidance3 and the free educational resources available from THINK AORTA. In Emergency Medicine, acute aortic dissection needs to be included in differential diagnosis more frequently, especially for chest pain. In Radiology, the barriers to obtaining an urgent CT scan of the Aorta (the only definitive way of diagnosing an aortic dissection) need to be removed.

Legal professionals should also familiarise themselves with the current standard of diagnostic care in acute aortic dissection, so that they are best-placed to support individuals and families who turn to them for help when affected by this condition. Where a complaint may be required, we have attached a guide to assist5.

Aortic Dissection is an emergency that is often fatal when missed. Early diagnosis is vital to successful treatment and improved survival of patients, however the signs and symptoms are variable, which can make diagnosis difficult. Typical symptoms include sudden, severe chest pain, which can be mistaken for a heart attack or pulmonary embolism. This, in addition to a general lack of awareness of aortic dissection among non-specialist clinicians, can lead to delayed or missed misdiagnosis. A study by the Mayo clinic found that 38% of patients with an AD are initially misdiagnosed and that in 28% of patients, the correct diagnosis was not made before post mortem examination6.

Our accredited THINK AORTA learning resources are available as a free download for any healthcare professional who wants to use them and we know they have saved lives.

Resources:

THINK AORTA

www.thinkaorta.net

Aortic Dissection Awareness UK & Ireland

www.aorticdissectionawareness.org

RCEM Learning resources

www.rcemlearning.co.uk/foamed/aortic-dissection/

References:

[1] Prevention of Future Deaths Report, Paul Sartori https://www.judiciary.uk/prevention-of-future-death-reports/paul-sartori/

[2] Delayed recognition of acute aortic dissection, HSIB Investigation Report, January 2020 www.hsib.org.uk/investigations-cases/delayedrecognition-acute-aortic-dissection/final-report

[3] Diagnosis of Thoracic Aortic Dissection in the Emergency Department, RCEM/RCR Best Practice Guidance, November 2021 tinyurl.com/DiagnoseAD

[4] National Adult Cardiac Surgery Audit, NACSA, Summary Report, 2023 (page 19) www.nicor.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/10633_NICOR-Annual-Summary_NACSA_v4.pdf

[5] Action Against Medical Accidents (AVMA) complaint leaflet www.avma.org.uk/?download_protected_attachment=Complaints-England.pdf

[6] Spittell PC, Spittell Jr JA, Joyce JW. et al. Clinical features and differential diagnosis of aortic dissection: experience with 236 cases (1980 through 1990). Mayo Clin.Proc.1993;68:642-651. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8350637/

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur.

Block quote

Ordered list

Unordered list

Bold text

Emphasis

Superscript

Subscript