Colin Holburn, Consultant in Emergency Medicine, Sandwell & West Birmingham Hospitals NHS Trust

A few years ago, I spent part of an enjoyable summer holiday reading two similar but different books. Both books chronicled the experience of the pilots involved in two aircraft accidents. The first was Miracle on the Hudson1; the second Thirty Seconds to Impact: The Captain’s Story of Flight BA382. Both accidents resulted from loss of engine power, and the reasons for the losses were outside the control of the pilots: one due to a bird strike; the other to contamination of the fuel when it was needed on landing. The treatment the pilots received afterward, however, was vastly different. One was feted as a hero; the other was the subject of criticism for months until the investigation into the cause of the engine failure was complete.

Why start an article on medical negligence and expert witnesses with this anecdote? Well, my attention was drawn to a publication by Medical Protection3 to encourage clinicians to put themselves forward as expert witnesses. However, this publication also contained the following paragraph in the introduction:

A secondary aim of this paper is to set out an argument for consideration of systems issues to be included as standard in expert reports. Too often, the current approach following an adverse incident places the emphasis on scrutinising the actions of an individual. However, it is rarely the case that a single individual is solely ‘to blame’; wider systems issues are often implicated.

In the last year, NHS Resolution has also started to produce reports on themes in clinical negligence and some of the first of these were in my area of clinical practice and expertise. One of these – ‘Missed Fractures’4 – was the second of three reports reviewing 220 emergency department claims. It highlights that while emergency medicine accounted for around 11% of notified claims in 2020/21, it only accounted for 5% of the potential value of the claims for the same period.

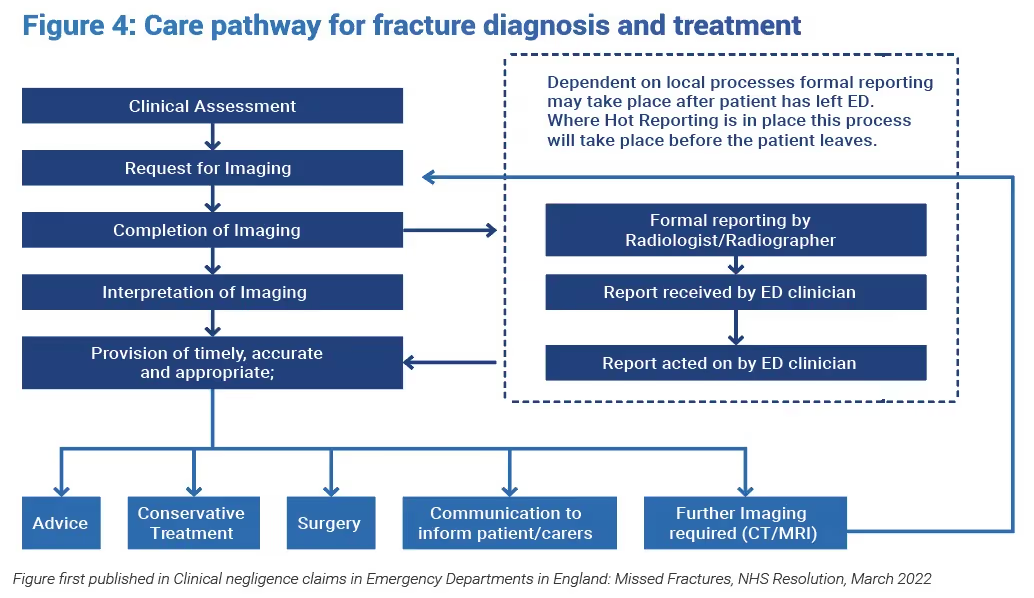

The report also includes a pathway for the management of fractures (See Figure 4 from p.18 of the report reproduced here), which has a number of discrete elements from initial presentation to an emergency department to completion of a definitive diagnosis and treatment plan. The pathway can potentially involve a number of clinicians in an individual patient’s journey as well as a number of technical stages and feedback opportunities to aid correct diagnosis and management plan. Inevitably, such a pathway can result in not just individuals making errors sufficient to meet the legal standard of being below a reasonable standard of care but also system failures where patients do not receive the correct treatment because the system of passing a patient along the agreed pathway is interrupted, even though no individual clinician’s management fell below a reasonable standard of care.

This pathway in the NHS resolution report, therefore, can be used to look at whether the assertion of Medical Protection in their policy document is correct and whether systems, rather than individual clinicians, should be more closely scrutinised when an expert is preparing a clinical negligence report.

Let’s look at each of the pathway stages in sequence.

Clinical assessment

The initial clinical assessment of a patient suffering from a traumatic injury normally involves an interaction between the patient and an individual clinician. In limb injuries, the clinician can be from a variety of clinical backgrounds: medical, nursing or paramedic. A history is taken from the patient and the patient examined.

Clearly, this interaction is between two individuals and, if there is a subsequent allegation of negligent care, this interaction is one of individual responsibility in most cases. However, with the pressure on emergency departments and increased waiting times, the amount of time available for clinical assessments may be reduced as the clinician feels under pressure to see patients in a timely manner. Therefore, the assessment may be limited in scope because of the system pressure the clinician feels under.

X-ray request

Following the clinical assessment, the NHS Resolution pathway requests an X-ray. This is reasonable if there is suspicion of a fracture as X-ray is a common initial investigation. However, the clinician may decide not to X-ray the patient. If the patient then later returns with a fracture, it may seem there was a negligent error in failing to undertake an X-ray.

Some fractures may not need any specific treatment. Indeed, if the clinician has followed national guidelines for X-rays such as the Ottawa knee or ankle guidelines, can the failure to undertake an X-ray be considered an individual error?

The pathway also assumes an X-ray request always follows a full clinical assessment. With the waiting times in emergency departments, some departments allow experienced triage nurses to send patients for an X-ray before the full clinical assessment. This can lead to errors if an inappropriate area is X-rayed due to a limited triage assessment or the patient giving a generic description of the injury, which may be different to that given to an assessing clinician.

For example, the standard X-ray views in a hand injury are anteroposterior and oblique views. While these views are helpful for many hand fractures, some finger fractures are often best seen in a lateral view and may not be apparent in the oblique views. This could be seen either as an individual error by the requesting clinician or as a system error in that process was implemented to improve patient flow while potentially undertaking imaging with limited information.

Interpretation of the X-rays

After the X-rays are available, they should be reviewed by a clinician. A potential for error is in reviewing an X-ray before the clinical assessment and assuming that it is either a correctly taken X-ray or that it does not show a fracture. This can lead to failure to undertake a comprehensive clinical assessment due to the clinician looking at an X-ray and seeing no fracture creating a cognitive bias in the clinician.

If a clinical examination is below a reasonable standard, looking at the wrong part of the X-ray films may cause a clinician to miss a fracture in another part. It is vitally important that the clinician adopts a systematic approach to interpreting X-rays and to in particular look carefully at the edges of the image.

We can see, then, that if a clinician reviews a correctly taken X-ray and misses a fracture, then this is an individual error. However, if a clinician reviews the wrong X-ray or an X-ray taken with an inadequate view, then this is a system error, caused by additional views not having been taken due to the information on the request or the interpretation of the request by the radiographer.

Formal X-ray reports

It is a risk-management practice for X-rays undertaken in the emergency department to be formally reported by a radiologist or reporting radiographer. Most emergency departments have a reporting standard of 48–72 hours and, in some departments, there is what is called ‘hot reporting’, whereby X-rays are reported in real time. In this scenario, the clinician may rely on the ‘hot report’ rather than reviewing the X-rays, but every clinician can make errors in reporting, particularly if the X-ray taken is not the correct one.

This is a system error as if the wrong X-ray is undertaken, and reported as not showing a fracture and this is relied on by the clinician who does not undertake a sufficient examination to elucidate that the X-ray taken did not show the injured part or the fracture sufficiently.

A further potential system error is when, rather than being done in real time, reporting is delayed, possibly due to staff shortages for a period longer than is optimum.

A fracture missed by the clinician and picked up in the delayed formal report may be too late for simple remedial actions to treat the fracture. This may lead to the patient having to undergo more extensive treatment that would have been necessary had the fracture been picked up by the clinician or the report had been prepared in a timely manner.

A final problem with the formal reporting system is that, even if a report is prepared in a timely manner and identifies a fracture not recognised by the assessing clinician, there can be a delay in the report being returned to the emergency department for review and further action by the consultant. However, this is becoming less common with the introduction of electronic patient records and electronic reporting and messaging.

I have been involved in more than one case where there was a timely formal X-ray report indicating a fracture not being picked up by the clinician, but no accompanying audit trail as to why the patient was not informed or asked to return for further assessment. Hopefully, with an electronic audit trail, an expert witness can try to unravel where the failure occurred if such a situation arises in a future case.

Treatment options

The treatment of fractures can be wide-ranging – as noted in the NHS Resolution report – from simple advice and conservative treatment to operative treatment, either immediately or after a delay, and possibly further investigations.

Patients can also be referred immediately to specialist teams for ongoing care or can be referred to an outpatient follow-up clinic for further assessment and treatment. Whenever an individual clinician makes a treatment decision, this is their own – or the clinician whom they ask for advice – responsibility. As such, this is not then a system error but a decision of an individual clinician, which could be found later in court to be below a reasonable standard of care. However, whenever a patient is transferred from a department or by a clinician, there is always potential for a system error, leading to delay or compromise of their treatment.

Making appointments for patients involves not only clinical staff, but also administrative staff and either a manual or a computerised booking system. If a patient has to be sent the date and time of the appointment, there are a number of potential system interventions that can lead them not receiving that appointment or them not attending at the correct time. If the patient then later makes a claim, indicating that nonattendance was due to not receiving the appointment or receiving it too late, it may be difficult for the Trust to show their system was not at fault unless there is a very good audit trail showing all the steps required to make sure the patient was sent the appointment in a timely manner.

One of the key messages in the NHS Resolution report is that it is reasonable and responsible that treatment options are communicated to the patient or their carers if they are children or vulnerable adults.

Many emergency departments have written advice sheets for common injuries to give to patients, particularly stating when they should seek further medical attention. While this is the responsibility of the clinician who assesses the patient, some treatments, such as the application of plasters, are done by a clinician who did not initially see the patient. There is a risk, therefore, that each clinician may think it is someone else’s responsibility to give such advice and so the patient may not receive the correct safety-netting advice. It is important that within the emergency department system each clinician considers it their responsibility to advise the patient. This should be captured in the standard operating procedures, so there can be no doubt what the system requires of individual clinicians – a recommendation made in the NHS Resolution report.

Conclusions

Clinical-negligence claims can be stressful for individual clinicians, as recorded in the Medical Protection report. The NHS Resolution report indicates the importance of training for the clinicians who undertake clinical assessments and radiological reporting, and, together, these improvements may help to reduce the individual’s responsibility in claims.

However, the role of system factors within the care pathway – particularly when there are several interrelated stages – can also lead to poor outcomes for the patient, even when each of the clinicians involved has undertaken their individual responsibilities in a reasonable manner.

Trying to unravel system failures in a complex system can take time. When preparing an opinion, the expert witness needs to consider all the potential system failures, which are not attributable to an individual clinician acting below a reasonable standard of care.

References:

[1] The survivors of Flight 1549, Miracle on the Hudson Ballantyne Books Dec 2010

[2] Peter Burkill, Thirty Seconds to Impact: The Captain’s Story of Flight BA38 AuthorHouse Mar 2010

[3] Medical Protection, Getting it Right when Things go Wrong: The Role of the Expert Witness medicalprotection.org

[4] NHS Resolution, Clinical negligence claims in Emergency Departments in England, Missed Fractures NHS Resolution March 2022 https://resolution.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/2-NHS-Resolution-ED-report-Missed-Fractures.pdf

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur.

Block quote

Ordered list

Unordered list

Bold text

Emphasis

Superscript

Subscript